The Women of Acadia

A historical reenactor at work in a very real kitchen garden at Louisbourg

Acadian history is often told as if it consisted solely of the exploits of men. However, we cannot explain the durability of Acadian culture, through all its trials and during a devastating diaspora, without understanding the women who were instrumental in keeping that culture alive through the generations.

It was a culture that fostered strong women. Weaklings didn’t last on the frontier. Yet the coutume de Paris, the law regulating such matters, decreed that women were to be treated as minor children, subject to their husbands and unable to own property in their own right or make contracts without their husband’s consent. Marriage contracts could provide the bride with broader rights and benefits. But generally, the coutume kept women legally subservient in the New World as it did in Paris, throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

The law, however, did not dictate personality. Women of Acadia could be as individual in their opinions and actions as women of today, if legally they had fewer options. Some, like Jeanne Motin, wife of two Acadian governors in succession, were conventional in outlook. Jeanne was apparently a quiescent woman who bore thirteen children during her two marriages, and thus became the progenitor of generations who can still trace their Acadian lineage to her.

Others were more forceful, like Marie-Madeleine Maisonnat. Though born to a Catholic family in Port Royal, she demonstrated her individualism by marrying a British lieutenant in a Protestant ceremony after Port Royal was taken by the British. Later in life, she was said to have presided over councils of war at Port Royal (renamed Annapolis Royal by the British), during conflicts with the French, her countrymen.

Three of Marie-Madeleine’s daughters also married outside the faith, though they were said to be “of the Romish persuasion” themselves. Elizabeth Maisonnat married John Handfield, who would later oversee the deportation of Acadians in the Annapolis Royal area. We have to wonder what tensions plagued their dinner-table discussions during that episode.

It was not a sign of independence, as is sometimes supposed, that an Acadian woman typically kept her maiden name throughout her married life. This was simply a custom of France that migrated to the New World. Only when she became a widow did a woman take her husband’s surname. At that point, she also regained full guardianship of her children, as well as control of the assets she brought to the marriage and such other marital property as was not allocated to her children.

If the marriage produced no offspring, the woman (or man) could demand an annulment. After an examination by a doctor and a midwife, if a “defect in conformation” was found, the marriage would be annulled and the infertile partner would be prohibited from marrying again, on pain of excommunication. On the other hand, if no defect was found, or if the demand was rejected for other reasons, the couple would be ordered to live together as husband and wife. Divorce wasn’t a thing in those days.

A girl’s class determined her level of education. If her family were prosperous, she might be sent for a time to the convent school at Louisbourg, where she would learn the tenets of the Catholic faith, along with sewing and other household arts. She would also learn penmanship and reading.

Daughters of farmers and traders learned what they needed at home, and were likely to be illiterate, as were their parents. They did the family weaving and baking, grew the kitchen gardens, worked in the fields at harvest time, helped raise younger siblings, and learned the midwife’s art to treat their families’ maladies.

We begin this section with the story of Francoise-Marie Jacquelin, a young French woman who lived an adventurous life as the bride of one of the first governors of Acadia, and died after defending her home from her husband’s archenemy in hand-to-hand combat in the 1600s.

The Most Remarkable Woman

She has been called many names: The Lioness of Acadia, a dazzling star, a virago, an actress (shorthand for prostitute) or the illegitimate daughter of one, a perpetrator of rebellion, a heroine. Something about Françoise-Marie Jacquelin lent itself to hyperbole.

Her life, romanticized in fiction, must have been incredibly difficult to live. It was certainly filled with adventure and intrigue. She was one of the first European women to make a life in Acadia, arriving in June 1640 at the age of 18 to marry a man she likely had never met. Her tenure there was short, less than five years, and almost all of it was spent in conflict.

There were only two European settlements pn the peninsula that would prove to be permanent. Both were sparsely populated, unable to offer much in the way of culture or community with other women. But Françoise-Marie seemed to thrive there.

She was a woman of abilities. She managed the couple’s fur trading business when her husband was away, charmed the stiff-necked Puritans of Boston, twice pleaded her husband’s cause before powerful ministers at the French court, made a daring escape from Paris in disguise, sued and won her case against a man who had broken a contract with her, engaged in hand-to-hand combat when her home was besieged, and died under mysterious circumstances as a captive of her husband’s mortal enemy.

None of her story is told in her own words. Françoise-Marie left no journal, no personal correspondence, no record of her innermost thoughts or feelings. Even her husband left no memoire of her, being, as one writer put it, “a man of the sword rather than of the pen.”

We don’t even know what she looked like. Though she was reputed to be a beauty, no portraits of her exist.

Here's what the public record tells us:

Early Life

Françoise-Marie Jacquelin was born July 18, 1621, in Nogent-le-Rotrou, France. She was baptized the same day in the town’s Catholic church, Notre Dame des Marais.

Baptismal record from Notre Dame des Marais. It begins “The 18th day of July sixteen hundred twenty-one was baptized a girl named Françoise, daughter of Jacques Jacquelin…”

We know that her father was a doctor of medicine. Her early life would have been comfortable, though not luxurious. We know that she could read and write, so she and her sisters, Gabrielle and Louise, must have received some level of formal instruction. We know nothing else of her childhood.

The Religion Question

There has been some debate about the Jacquelins’ religion. Some writers contend that they were Huguenots, French Protestants, and that their affiliation with Catholicism was politic. If so, keeping their religion secret would not have been unusual for the time.

Religious tensions in France ran high during Françoise-Marie’s lifetime. When she was still a child, the formidable port city of La Rochelle, a Huguenot stronghold, was besieged by Cardinal Richelieu’s forces for refusing to submit to the Catholic King Louis XIII. The city was bombarded relentlessly, its port blockaded, and its population starved into submission, decreasing from 27,000 to 5,000 in 14 months.

In such an environment, it served Protestants to make an outward show of conformity to the dominant religion. We do not know whether this is true of the Jacquelins. If conformity is compulsory, it is impossible to know when it is sincere.

Moreover, it was common for enemies to accuse one another of being Protestant, which was akin to treason, regardless of evidence to the contrary. Such accusations were raised against Françoise-Marie in the New World, and they persist, unsubstantiated, through the years, confusing the record.

What we know for certain is that the Jacquelins’ marriages and baptisms were solemnized in the Catholic faith, including those of Françoise-Marie.

Marriage Contract

She next appears in the public record on December 31, 1639. On that date, at the age of 18, she signed a contract to marry 46-year-old Charles St. Étienne de La Tour, governor and lieutenant-general of Acadia. His royal commission gave him control of France’s lucrative fur trade from his fort on the St. John River (Rivière St. Jean) in New Brunswick. He first arrived in Acadia as a teenager and lived for a time among the native Mi’kmaq. He had been married once before to a Mi’kmaq woman whose name is lost to history. She gave him three daughters before her death, all of whom were raised by their father.

Although he periodically returned to France on business, La Tour was not present to sign the contract. There is no indication that he and Françoise-Marie met before their wedding. When he wanted a European bride, he enlisted his steward, Guillaume des Jardins, to find one for him. Des Jardins’ power of attorney authorized him to select “a marriageable person suitable to our circumstances” but did not name Françoise-Marie as that person.

The marriage contract was generous to the bride, who was active in negotiating it. La Tour did not require a dowry from the Jacquelins. Instead, he promised Françoise 2,000 livres before the wedding, to purchase jewelry and anything needed for her comfort in the New World. (An addendum to the contract revealed that the funds had been received.)

After the wedding, the bride would receive 10,000 livres from her husband. She would be entitled to half the goods acquired during the marriage, as was the custom in France. The groom also provided her with two maids and a manservant. The Jacquelins were required only to purchase the bridal trousseau.

One extraordinary provision declared that, should frontier life not agree with Françoise, she would be allowed to return to her family or wherever she wished, with all the gifts she had already received, and an additional 8,000 livres.

Formalities concluded, Françoise had only to await good sailing weather to meet her groom. On March 26, 1640, she left La Rochelle aboard L’Amitye de la Rochelle. Despite La Tour’s inducements, it must have taken courage to step aboard that ship. After all, she was beginning married life with a stranger more than twice her age, in an inhospitable wilderness, knowing nothing of the local languages and customs, and where she would lack the comfort of other women of her station.

Moreover, the crossing was difficult and could last months. Sailing ships of the day were at the mercy of the wind and waves. During storms, passengers could be tossed about day and night in their cabins, which were airless and uncomfortable to begin with. Or they could be becalmed for days at a time, while nerves frayed and supplies ran low.

It might also have seemed ominous to Françoise that the bridal ship carried the materiel of war—nine cannon, three mortars, 16 muskets, 24 pikes, and ammunition for her husband’s fort.

Why did she make the journey? She must have had suitors at home. She was young and beautiful, and her family could provide a respectable dowry. Was she perhaps too unconventional, too educated for her provincial neighbors? Was the strong character that revealed itself in Acadia too forceful for them?

Or do we wonder about her motives only because she was a young woman? The New World was a magnet for risk-takers. May we not believe that Françoise welcomed the chance to pit herself against the challenges she would find there? Or are we to believe that courage and the excitement of the unknown are reserved to men?

Arrival in Acadia

We know for certain that Françoise-Marie Jacquelin married Charles St. Étienne de La Tour in Acadia in June 1640. The location of the ceremony, like so much else about the bride’s life, is in debate. Some historians place it at Port Royal (present-day Annapolis Royal). But Port Royal was the stronghold of La Tour’s archenemy, Charles de Menou d’Aulnay de Charnissay. Though there was a Catholic mission nearby, it is unlikely that La Tour would risk a confrontation on his wedding day by sailing there.

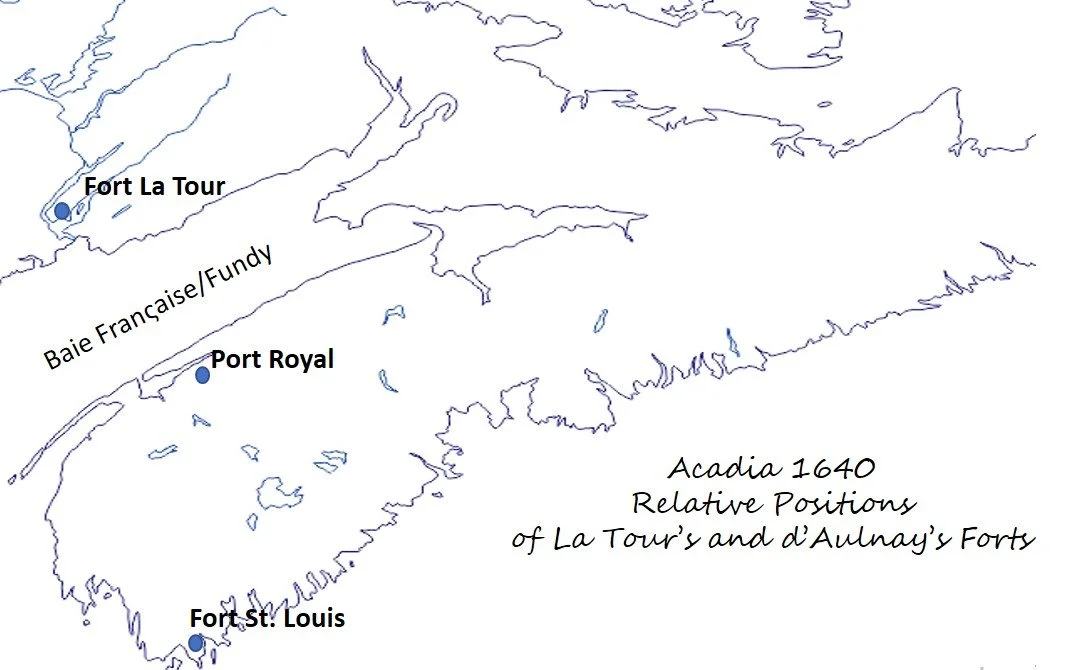

The marriage contract stipulated that the wedding would take place at Fort St. Louis, a stronghold built by La Tour’s late father. As a family possession, and given its location on the southeast coast of Nova Scotia, well out of d’Aulnay’s immediate reach, it seems a more likely wedding venue.

Sources agree that the marriage was solemnized by missionary priests, after which the couple set off for Fort La Tour (also called Fort Ste. Marie) in New Brunswick. The fort was located where the St. John River meets the Bay of Fundy (Baie Franςaise to the French). From that strategic location, La Tour could ply his trade in the interior of Canada, while the bay gave him access to Europe’s and New England’s markets.

The fort stood on a low hill above an inner harbor. The year before Françoise arrived, La Tour enlarged the compound to 120 square feet. Its palisade enclosed a trading post, a cookhouse, a forge, storerooms for furs and munitions, and a chapel, as well as living quarters for the governor and his wife, and for the troops and workers. There might have been a kitchen garden inside the walls as well, though staple crops would have been grown outside the enclosure. The number of residents varied over time, from an estimated 200 to fewer than 50.

Suitable to the Circumstances

The young bride soon proved a capable partner to her husband. They were well matched in intelligence and energy. They could both be charming, though Charles was perhaps more hot-headed than Françoise, who proved a capable diplomat.

La Tour was frequently away, leaving the management of the trading post and the household to his wife. To anyone else, the trading post alone might have seemed a daunting responsibility. It is all but certain that Françoise had never seen an indigenous person before. At the fort, she would have been surrounded by dozens of them at a time. She would have heard a mélange of languages and dialects, as native Mi’kmaq, Maliseet (Wolastoqiyik), and Passamaquoddy mingled with European trappers from several countries, all of them arriving in canoes piled high with beaver, otter, caribou, or bear pelts.

Françoise had to learn to value the furs based on condition and species, to barter for the best trades, and to keep the accounts. She had to know how to stand up to some rough characters, and gain cooperation from people whose customs and manners differed greatly from her own.

Civil War

Another important concern was the defense of the fort and its denizens. Soon after her arrival, Françoise found herself embroiled in what became the central fact of her life in Acadia—an intense rivalry between her husband and Charles d’Aulnay. Their feud was the centerpiece of what became known as the Acadian Civil War, which lasted until d’Aulnay’s death in 1650.

D’Aulnay was a Catholic, a naval captain, and a prosperous trader who held the seigneurie (land grant) of Port Royal, only 45 miles across the Bay of Fundy from Fort La Tour. As a nephew of the powerful Cardinal Richelieu, he was well connected at the French court. He was also an intelligent and dangerous adversary, and a rival of La Tour’s in the fur business.

Charles d’Aulnay de Charnissay. There are no portraits of his rival, Charles de La Tour.

D’Aulnay’s enmity toward La Tour began years before Françoise-Marie arrived. It reportedly started over possession of a prosperous trading post at Pentagouet, in present-day northern Maine. Built by La Tour’s father, it was captured by New Englanders and later retaken by d’Aulnay. Possession was then transferred to La Tour by the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, which was both a mercantile and a colonizing organization. D’Aulnay apparently never forgave the company, or La Tour.

Eventually, his wrath would extend to Françoise-Marie, who was markedly different from his own wife, Jeanne Motin. His description of Jeanne as a “devout and modest little servant of God” indicated that she stayed within the sphere allotted to obedient women. Françoise was far less docile. D’Aulnay later had no compunction about reviling her as a person of low character, and even insulting her father, to gain advantage over her husband at court.

For his part, La Tour did his best to keep the feud alive. In July 1640, less than a month after their wedding, bride and groom sailed across the bay to Port Royal in two ships. On arrival, La Tour sent a message ashore, demanding to inspect d’Aulnay’s store of furs. He may have believed he was within his rights as governor, which gave him sway over “all the coasts and province of Acadia.” However, the second ship might have been meant to carry off d'Aulnay’s pelts, which weren’t rightfully La Tour’s.

Accounts of what happened next are murky. Apparently, d’Aulnay was absent, and his steward refused to let the couple land. One report says that as La Tour left for home, d’Aulnay returned and their ships confronted one another. All accounts agree that cannon fire was exchanged, and the bride and groom were captured. D’Aulnay released them only after forcing La Tour to sign an admission that he fired first.

D’Aulnay sent the confession to France, without mentioning that it was given under duress. When the king’s ministers received it, they suspended La Tour’s rights and demanded that he return to court to answer for himself. Richelieu then conferred the governorship of Acadia on Charles d’Aulnay.

It was the first of two instances in which d’Aulnay would use his influence at court to La Tour’s detriment. Each time, La Tour was ordered to Paris to answer the charges, and each time Françoise-Marie went in his stead. Had La Tour gone, Richelieu’s men would have arrested him.

Envoy to the Royal Court

Jean Armand de Maillé, Duc de Fronsac

.

On the first occasion, Françoise set sail for France in September 1642. She found the French court in disarray. Richelieu was dying. Political alliances were shifting. When the cardinal went to his maker in December, another of his nephews, the Duc de Fronsac, became Grand Prior of France, with control of the country’s commercial interests, including Acadia’s fur trade. Françoise would have to make her case to him.

Fronsac was a formidable personage, a member of one of France’s most powerful families, and an admiral who had defeated the Spanish fleet at about the same time d’Aulnay held Françoise and her husband captive. Unintimidated by his grandeur, and armed with supporting testimonials, Françoise pleaded her husband’s cause. She must have been convincing. After hearing her arguments, Fronsac restored La Tour’s title and rights.

Again, Françoise waited for good sailing weather. In April 1643, she returned to Acadia aboard the warship St. Clement, bringing 140 soldiers and craftsmen, Catholics and Protestants alike, along with munitions and supplies.

She found d’Aulnay’s ships waiting at the mouth of the St. John. Her archenemy had blockaded the harbor just after her departure for France. Nevertheless, La Tour slipped past the blockade in a fishing boat, and reunited with his wife aboard the St. Clement where it lay in hiding down the coast.

It’s one thing to have rights; it’s another to keep them. Unable to return home, husband and wife sailed to Boston for assistance. There they made a show of courting the starchy Puritans. They attended Protestant religious services, admired the militiamen who drilled on Boston Commons, and charmed the leading citizens, including Governor John Winthrop. They networked with prominent merchants and financiers.

For their trouble, they were denied official support against d’Aulnay, but were allowed to privately lease enough vessels to break the blockade. In August 1643, when their little fleet sailed into the Bay of Fundy, d’Aulnay’s ships fled back to Port Royal.

Birth of a Son

At some point in this period, Françoise gave birth to a son, probably in Acadia. They named him Charles Françoise-Marie for both parents. It has been speculated that he was born sometime in 1643, though that is unlikely. By April of that year, Françoise had been away from her husband for eight months. If she had been pregnant when she left Acadia, she would have been near full term on the return journey. Given the rigors of travel, it isn’t likely she would undertake a voyage so near her due date. By September 1643, she was already on her way back to France, and would remain there until the following year.

It seems more likely that the child was born sometime in 1642, before Françoise left for France in September. If so, she would have left her infant son in the care of one of her female servants, perhaps enlisting a wet nurse from among the native women. Her son’s baptismal record, registered in the family parish in 1645, does not give a date or place of birth, mentioning only that he was “environs de deux ans” (around two years old).

Renewed Hostilities

In August 1643, when La Tour’s envoy presented renewed credentials to his rival, d’Aulnay received them with contempt, refused to open them, and sneered at La Tour’s overtures of peace, which probably weren’t sincere anyway. Angered, La Tour attempted to land a combined Acadian-Bastonnais force at Port Royal. After a minor skirmish that served only to heighten tensions, La Tour withdrew.

Again, vitriolic reports and accusations from d’Aulnay flew across the Atlantic. Again, La Tour was censured in Paris, even more severely than before. Again, in September 1643, Françoise sailed for France to plead for her husband.

That time, her arguments were less successful. She was allowed to send La Tour a single ship with provisions for two months, but she was ordered not to leave France on pain of death, hostage for her husband’s return.

What happened next proved both Françoise’s courage and her resolve. She left anyway.

She slipped out of the country in disguise, bound for England where, in late March 1644, she hired the ship Gillyflower and loaded it with supplies. However, its captain, Jean Bailly, dithered, sailing up the St. Lawrence River and stopping for months to fish off the Newfoundland banks, so that it was again September before she finally glimpsed the Nova Scotia coastline again. Even then, she wasn’t home yet.

Ever vigilant, d’Aulnay spied the Gillyflower as it approached, and bore down on it in a vessel armed for war. While Françoise hid below deck, Bailly convinced d’Aulnay that he was bound for Boston. D’Aulnay gave him some correspondence to deliver there, and let him go. Thus, in late September, 1644, Françoise found herself once again in Boston, only to learn that La Tour had been in town but had departed eight days earlier.

Another woman might have despaired, but Françoise kept her head. She would need money and friends. First, she sued Bailly in the Massachusetts court for delaying her return. Then, while she awaited the decision, she studied the Puritan faith, whether to curry favor with her hosts, or out of a long-held love of Protestantism, is unknown. It was an act that would later help seal her fate.

She eventually won her lawsuit, and collected part of the sum awarded to her before Bailly fled Boston. With what money she recouped, Françoise provisioned three ships and braved December storms to return to her husband and son. Because d’Aulnay had lifted the blockade due to the weather, she finally made it home.

The Final Struggle

The situation at Fort La Tour was dire. Civil war had kept its denizens from hunting and tending crops, and the arrest warrants curtailed La Tour’s ability to sell his pelts in France, while the blockade had kept him from trading elsewhere. As winter dragged on, necessities such as flour, meat, corn, ammunition, and even candles were in short supply. La Tour was unable to pay his men, some of whom defected to Port Royal. Those who remained began to starve.

Early in 1644, a desperate La Tour again left for Boston to secure aid, leaving Françoise in command of a diminished garrison, where conditions continued to deteriorate. Nerves would have been close to the breaking point. Perhaps for that reason, Françoise quarreled with the Recollet priests at the fort. Possibly, they objected to her interest in Puritanism and she objected to their objections. Finally, they deserted her, taking some of her men with them to Port Royal.

When he learned of La Tour’s absence, d’Aulnay prepared to lay siege to his enemy’s fort while La Tour was still in Boston. By April, he was ready. His ships took up position in the inner harbor and bombarded Fort La Tour. It was an unequal fight from the start. The guns on his flagship alone outnumbered those of the garrison.

As with so much else, accounts differ as to how long the battle raged. D’Aulnay claimed it lasted only a day; others reported that it continued for three days and three nights.

At first, Françoise’s cannon held him off. When they damaged his flagship, he pulled out of range, allowing her to take stock of her position. Her supplies and ammunition were nearly exhausted; her men were surely so. Fires would have broken out within the walls, where the bodies of the dead would have lain unburied.

Then, d’Aulnay returned and landed guns outside the fort’s walls. They broke a parapet, and the attackers poured over the top. Desperate hand-to-hand combat ensued. The defenders used rapiers, pikes and halberds, led by Françoise-Marie who, according to legend, fought valiantly among her men.

At last, outnumbered, exhausted, and outgunned, Françoise-Marie agreed to surrender, on condition that her men be given quarter.

D’Aulnay accepted her terms. But when he took possession of the fort, he proved himself a true villain. He broke his word. On Easter Day, 1644, he erected a gallows and sentenced her surviving men to death. One man escaped by agreeing to be hangman to his fellows.

There was no escape for Françoise. In a show of barbarity, d’Aulnay tied her to a stake and forced her to watch with a rope around her neck as, perhaps one or two at a time, men who had remained loyal to her died a slow death by “hanging and strangulation,” struggling against the noose for several minutes before dying.

Death and Legacy of a Heroine

According to reports by d’Aulnay’s men, d’Aulnay took Françoise prisoner but gave her the liberty of the fort, until she tried to send a message to her husband. Then he tightened control, locking her in the fort’s dungeon. This version conveniently places blame for d’Aulnay’s subsequent treatment of her on Françoise-Marie herself, as if, had she been a better prisoner, he might have been lenient.

To my reading of his character, it is more likely that d’Aulnay tossed her into the dungeon immediately, showing her the same cruelty he had shown her and her men earlier.

Reports from the Capuchin friars and other contemporaries tell us she died three weeks later, in circumstances her captor never explained. Romantics say she died of grief. Perhaps she did, but I believe her heart was too stout for that, even after all she suffered. The Capuchins thought she was poisoned, and that is plausible.

It is also worth noting that three weeks is approximately the time it takes an adult to die of starvation. It seems entirely feasible that d’Aulnay decreed a slow, painful death for the unconventional woman who dared to challenge him, as he had for her men.

She was 23 years old.

The Capuchins reported that she was buried outside the fort, near the soldiers who died before her. Although archaeologists unearthed the fort’s foundations three centuries later, those graves have never been found.

Her son did not survive to carry her legacy forward. He was sent to France and adopted by her sister Gabrielle and Gabrielle’s husband, who apparently had no children of their own. The boy may have died young. After his baptism in 1645, he disappears from history.

Who Was Françoise-Marie?

So after we know all that we can know of Françoise-Marie Jacquelin, what do we really know? The character I sketch from the record is this: She was an intelligent woman who was as ambitious and competent as the men who knew her, or thought they did. She seems to have relished adventure, and was certainly equal to the challenges of frontier life. Being neither submissive nor soft-spoken, she defied the accepted role for women in some ways. Yet she used all her energy and ability to support her husband and home until the end. She could be uncompromising, yet she was diplomatic enough to win over the Grand Prior of France. As actors say of a particularly versatile colleague, she had range.

Françoise-Marie’s tenure in Acadia spanned less than five years. Although we know her only through records left by men, and although those records are sparse and often questionable, her truth speaks to us across centuries with resounding clarity. It tells of courage, commitment, resourcefulness, and perseverance. Through her short life, we glimpse the political, religious, and military intrigues of her day, on both sides of the Atlantic.

It’s also worth reiterating that all of Françoise-Marie’s great energies were exerted in defense of her husband and her home. Despite d’Aulnay’s assertion that she was “the cause of [La Tour’s] contempt and rebellion” she was never the aggressor. (I can’t say the same for her husband.) When her rights were challenged, Françoise-Marie stood on the parapets and fought.

One additional note: I am struck by the similarity between d’Aulnay’s response to this unconventional woman, and the vitriol directed at outspoken women of our day. Some men—not all or even most—respond to a strong woman with a viciousness that goes beyond misogyny. How ironic, then, that it is partly through d’Aulnay’s response to her that we can see how extraordinary this young woman was.

Perhaps her life was best summed up by historian George MacBeath, who wrote, “Here, truly, was the most remarkable woman in Acadia’s early history.”